Portrait of my parent

Vivienne Hill remembers her father’s sharp intellect, quick wit, and stunning artistic talent. She chronicles the heartache of seeing him deteriorate with dementia, but how his faith and spirit eventually won out.

They say you lose your parent to dementia or Alzheimer’s disease long before they pass. This is true, and years before my father was diagnosed, his personality changed and his ability to converse on subjects or hold deep conversations diminished over years. This was a sad loss, as my father had a great intellect and killer wit. His humour remained but was reduced to repetitive puns.

It is only in hindsight I can pick the year my father began his journey with dementia. Dad had a minor car accident and became obsessed with the details of the incident. He talked about it to the point of distraction. This was out of character for my fun-loving father, but I now see this as the first step in his mental decline.

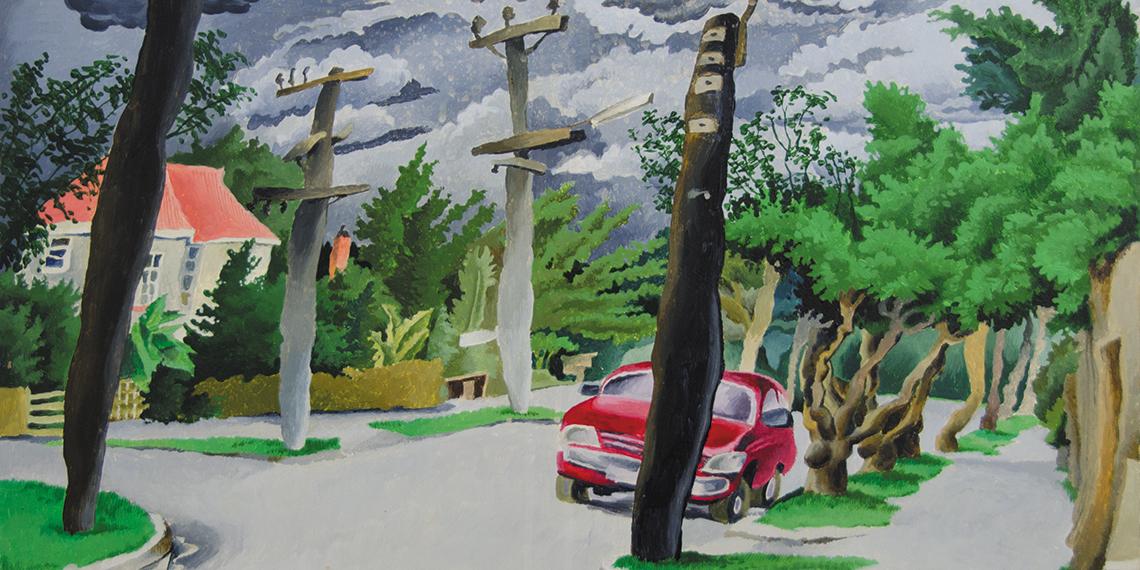

Prior to this accident, my father had retired and spent his days painting in his studio. My parents were originally Salvation Army officers, but they left so Dad could attend art school at the renowned School of Fine Arts, attached to the University of Canterbury. He was part of an illustrious alumni, but chose a career in advertising, though he still painted at every opportunity. Once retired, he was able to indulge his passion and was a prolific artist until a few years before he passed away.

In the early years of his dementia, my mother would cover for him—she prompted his replies, finished his sentences and changed subjects. In time, the stress and isolation of living with a partner with dementia became apparent. My concern for my mother grew as Dad declined, but she would not consider moving into supported accommodation. Mum passed away before Dad, and I often wonder if the strain of caring for him precipitated her failing health.

Dad was able to function day-to-day with the help of Mum, but once Mum passed away, we became fully aware of the extent of his deterioration. I did not live in the same city as my parents, so my visits were sandwiched between work and family commitments. There are no ‘text book’ dementia stories, the disease progresses at its own rate and I would notice declines each time I visited.

Dad was termed ‘a character’—he loved kids (he was a big kid himself) and dogs. All his quirky personality traits magnified as the disease progressed, to the point I could no longer take him to the supermarket because of his ‘off’ conversations with people.

He owned a yearly diary where he would record the events of the day, this included the time the sun rose and set, the maximum and minimum temperatures of the day, and what he ate. Entries became more detailed as his memory failed, but near the end of his life he forgot he owned a diary.

Dad continued to drive, very badly, though we made multiple attempts to discourage him. Two incidences happened to confirm the time had come to get Dad off the road. He lived on the North Shore of Auckland and wanted to pop over to a corps meeting in the next suburb to where he lived. Instead of attending the meeting, he forgot to turn off the motorway and drove over the harbour bridge all the way to the Bombay Hills.

I became aware of the second incident when we had a friend visiting from Auckland. I am not sure how we got onto the subject, but she told me about an elderly man who had flagged down her car on a main road near where my father lived. She stopped to see if he needed any help and he told her he had forgotten how to get home. She found his address in the car and directed him home. I asked her what the address was, suspecting it might well have been my father who had flagged her down, and, sure enough, it was!

Dad continued to paint, though his deterioration hastened after Mum died. The paintings were large, colourful and intricate, and I was amazed that even though his memory was gone he still managed to pick up the paint brush and produce these paintings. He steadfastly refused to go into care, even though he was not safe at home and nearly burnt the house down more than once. In the end, the decision to move him was taken out of his hands and ours.

One day one of my sons was visiting Dad—he often popped in to keep an eye on his grandfather. He knocked on the door—no answer. He looked through the opaque glass and saw his grandfather lying on the floor. He broke into Dad’s house and called an ambulance. The hospital assessed him and told us that Dad would not be returning home and we would need to find a retirement home for him. This is easier said than done, and it took us a few weeks to find and place Dad in a suitable home with a dementia wing attached.

I remember the day Dad no longer knew who I was. I had arrived in Auckland to visit him. I walked into the home and said, ‘Hello, do you know who I am?’

He said, ‘I know your face, but I can’t pick your nose’ (another pun).

‘Do you remember my name?’

‘No’, he replied.

You prepare for this moment, but I still felt sad.

Each time I visited, I would sit on Dad’s bed, take out a photo album we had prepared for him, show him the pictures of his family and tell him what each person was up to. He would not remember, but he enjoyed the process.

My mother always had a strong, vigorous faith, but my father’s faith was unconventional. They were life-long Salvationists, but Dad’s beliefs developed in a different direction. One of the outcomes of dementia, was that my father returned to simple belief and faith in Jesus Christ. It was childlike and accepting. It comforted me to know that even though Dad’s mind was ravaged by dementia, his spirit was not. He had an eternal part of him unaffected by disease. It did not wear out or age. There were frustrating times with my father, times when I needed to remind myself of this fact: Dad belonged to Jesus and Jesus would take care of him.

Near the end of his life, we were able to spend two weeks with Dad. He was unconscious for much of this, but at times he would waken, his cheeky sense of humour still intact. We would ask him:

‘Are you all right Dad?’

‘No, I’m half left’ …a typical Clive reply.

By Vivienne Hill (c) 'War Cry' magazine, 29 June 2019, p20-21 You can read 'War Cry' at your nearest Salvation Army church or centre, or subscribe through Salvationist Resources.