A Hero's Legacy Lives On

Des Adams grew up hearing about how The Salvation Army helped his father post-World War II, after he spent four years as a prisoner of war. As we commemorate the battle of El Alamein on 23 October, we remember a hero of the infamous ‘Desert War’, whose legacy lives on.

Walter Adams was 23 when he joined the Long Range Desert Group, which would eventually become the SAS. He was stationed in Libya, as part of the desert campaign against Italy who had joined forces with the Nazis.

Wink—as Walter was known to everyone, ever since as a child he used to ask for a ‘wink of water’—was tasked with undertaking reconnaissance far into enemy territory.

Lying under a camouflage net, he undertook 12-hour missions, painstakingly counting enemy troops as they marched by. This provided valuable information to the Allies about how many troops were needed in battle.

In February 1941, Wink and his patrol came under intense fire from Italian fighter planes. ‘Six trucks made it to relative safety, but Wink’s truck—the last vehicle—was hit by the aircraft. Both front tyres were punctured and the radiator holed,’ recalls Jan Adams, Wink’s daughter-in-law, who has done extensive research on his time in the war.

As Wink scrambled to change the tyres and fix the radiator, a stray bullet ricocheted off the truck’s chassis and killed their Italian prisoner of war (POW) in the rear of the truck.

Wink was captured 1000 miles into enemy territory. He was ‘missing in action’ for eight months, and no one knew if he was alive or dead.

Finally, Wink managed to send a broadcast over shortwave radio from his POW camp in Italy. ‘He said, “Please send a message to my mother, this is her name and address, please tell her I’m alive”,’ recalls Jan. Someone did hear the message, and his mother got the news just before Christmas.

Life as a POW

Like many typical Kiwi soldiers, Wink never talked much about his experiences as a POW. He was one of 9140 Kiwi taken as prisoner—equating to one in every 200 soldiers (a strange anomaly, since the world average was one in 1000).

‘Capture was a bewildering experience for most young New Zealand men. They had gone to war to fight, perhaps be wounded, even to die—but not to be captured. It never occurred to them,’ writes David McGill in his book P.O.W: The untold stories of New Zealanders as prisoners of war.

Letters home from POWs paint a picture of overcrowded conditions, dysentery, overflowing latrines, poor sanitation and lice. Beds were made of wooden slats and woodchip mattresses—but the slats were eventually used for firewood during the freezing winters.

One story Des remembers his father telling was that it was so freezing in the huts, a cup of water beside his bed would be frozen in the morning.

The camp at Sulmona in Italy, where Wink was held, crammed up to 80 men in its dormitories, with just a washroom, a few cold taps that only worked erratically and latrine buckets.

The diet consisted of bread rations, a little macaroni soup and tinned meat. When Italian rations declined in the winter, they relied heavily on Red Cross food parcels. But these dried up and the men ‘experienced real hunger’, says Jan. However, in letters home, Wink said, ‘he was being well treated and was in good health’.

With typical bravado, a letter to Nana Adams from Wink’s captain, Major Clayton, says: ‘I sincerely hope that—and think most probably—when the war is over you will get your son back with no more harm than a strong dislike of macaroni’.

Despite describing the Italian guards as ‘cruel and unkind’, Wink made the most of his time in the camp by learning to speak Italian and became a translator for the Allied officers.

The Long March

The turning point for the desert campaign came on 23 October 1942, at the second battle of El Alamein. This became a famous victory and swung the desert theatre in favour of the Allies. It was the ‘beginning of the end’ of fighting in the region.

By 1944, the war was coming to an end. In order to delay the liberation of the POWs, German authorities evacuated over 80,000 prisoners and forced them to march on foot westward, across Poland, Czechoslovakia and Germany. Wink was one of the soldiers that marched for four months on empty stomachs, and in one of the coldest winters of the twentieth century.

‘In poor condition, they had to march hundreds of miles in harsh winter weather, through a country devastated by war, bombed and strafed by their own forces, relying on elderly guards as badly off as themselves to forage for enough food to keep them alive,’ writes McGill. ‘Marching was a futile exercise which in some cases involved walking round in circles. It was their last and grimmest experience as prisoners, it was their final hurdle to freedom, it was an experience many would not survive.’

In his diary, Warrant Officer ED White wrote: ‘The sick were mounting every day, mostly bad feet, and general depression through malnutrition’. Frostbite was common and it is estimated 80 percent suffered from dysentery. The POWs did not know what was happening, and rumours abounded that they were being moved to concentration camps, or literally being marched to death.

But, as they reached Western Germany, the true state of the war was revealed. They were met by American troops, and were finally liberated. On 12 April 1945, ED White wrote: ‘Transport suddenly arrived to take us on our first journey home and what a welcome sight. Passed through bombed areas … given billets, coffee and doughnuts and a K-ration. Cannot believe one is going to be flown out of this country’.

Doughnuts were a treat made famous by The Salvation Army during World War I, as a simple way to nurture frontline troops. Wink and others may well have been given their share of doughnuts from The Salvation Army ‘lassies’, at one of the Army’s mobile canteens—travelling kitchens that provided refreshment for soldiers.

‘Fattened up’ by the Sallies

Wink was met by Salvation Army soldiers at the Belgium border, who ushered him to the safety of its recuperation homes in England. He was 11 and a half stone (73kg) when he went to war, and was seven stone (44kg) when he finally got to safety in Belgium.

‘All they needed was to be fed and fattened up, and that’s where The Salvation Army looked after him so well,’ says Jan.

‘The services provided by The Salvation Army were varied and developed over the course of the war, but primarily consisted of providing practical help to the serving forces, their families and the communities around them,’ says the archivist from The Salvation Army International Heritage Centre. ‘Following the end of the war, The Salvation Army’s work focused on providing relief in the aftermath.’

A training manual from 1945 states that the ‘Army will help mainly with mass feeding, distribution of clothing and clothing materials, child welfare, investigation, information and case work, e.g. tracing and reuniting missing relatives, etc. Circumstances in different countries vary considerably; but everywhere there are the homeless, ill-nourished, unhappy and almost hopeless people of all ages and classes needing practical care and help’.

Taking up the challenge

‘For the rest of his life, Dad could not praise the Sallies highly enough,’ says Des. ‘The Salvation Army made a huge difference to the way he thought about his life, because he always thought he was fortunate. In those days the Sallies used to set up near his business [with collection buckets], and he gave them a donation on a weekly basis.

‘That had an impact on me as a giver, definitely,’ adds Des. ‘He always used to say to us, “If you can ever do anything to help the Sallies, you have to do it”.’

Jan took up the challenge, doing door-to-door collections for The Salvation Army, before street collections began.

Jan and Des are both pharmacists, having owned successful businesses on the Hibiscus Coast and Albany, Auckland. ‘We’ve been very fortunate that the community has always supported us, so we want to support the community,’ explains Des.

‘During lockdown, The Salvation Army really stood out,’ says Jan. With ongoing border closures, they decided to sell their property used for international home exchanges, and donated furniture from the house to Family Stores.

When Des dropped the furniture off, he immediately saw it go to use. ‘When I got there, I was told that they were trying to find beds for a young woman they were getting into housing, because she didn’t have anywhere to go. So as soon as the beds got there, they immediately rushed to get them to her,’ recalls Des. ‘You walk away feeling very proud of yourself that you turned up with that bed.’

‘Where in lockdown would you turn to if you were that woman who didn’t have anywhere to go? You would turn to The Salvation Army,’ adds Jan.

So, when Jan and Des received the Winter Energy Payment, which goes to superannuants, they had an ingenious idea: ‘We got the heating subsidy and, quite honestly, we don’t need it. So I totalled it up, and The Salvation Army got down to the last cent what the government gave us for our power bill,’ laughs Jan.

She says that being able to give back gives their life meaning in their retirement years: ‘When you get to retirement age, you have to seriously think about what you’re going to do with your life, because there has to be something that gets you up in the morning. You can’t just sit around looking out the window, and charity work is what gives us purpose.’

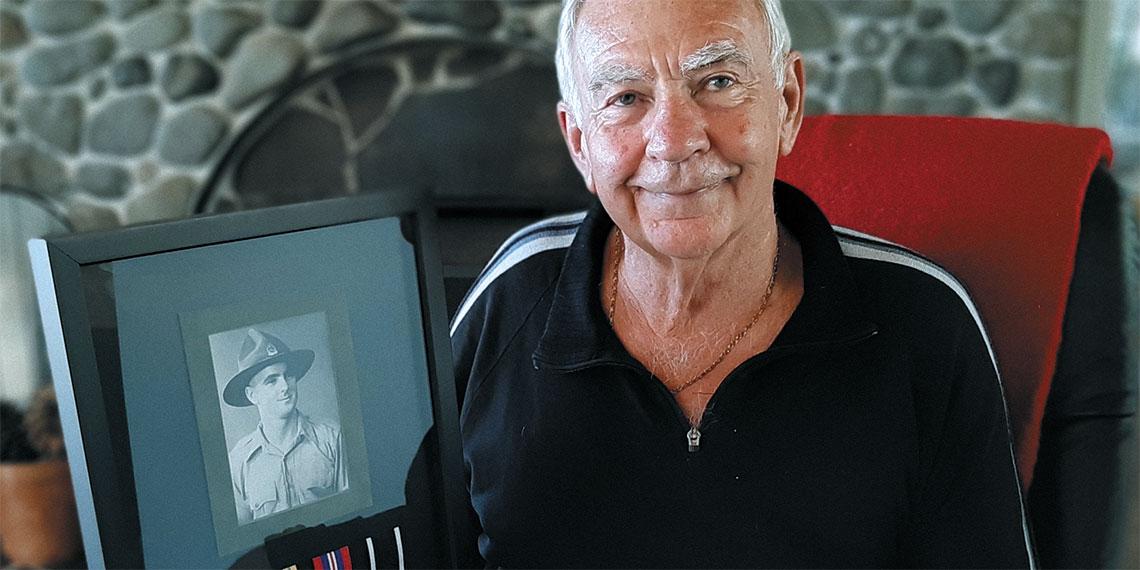

My father had quite an influence on my life,’ adds Des, holding Wink’s World War II medals. ‘And he always said he had been very fortunate.

‘We’ve also been fortunate that we’ve never needed the help of The Salvation Army, but also fortunate in that we’ve been able to give.’