Drugs, Gangs and Hope—The State of Our Communities

People in some of our most overlooked communities shared their hopes, dreams and raw, honest stories in a new Salvation Army report.

The second annual ‘State of Our Communities’ report by The Salvation Army Social Policy and Parliamentary Unit surveyed 603 people in six areas around the country about their community.

People in Kaitaia, Whangārei, Manurewa, New Plymouth, Hornby and Tīmaru were asked about the things they liked, and the concerns they had, about their community. They were also asked what they would say to the prime minister if they could talk to her, and what they would like to see change in the next five years, report author Ronji Tanielu said.

Most of all though, it was about giving people a voice, and people had shared honest, raw stories, Ronji said.

‘These quite powerful stories came out, people who had journeyed through addiction or homelessness. There was a 21-year-old guy in Whangārei who talked about how he lost his parents in a car crash caused by a drink driver, how he became addicted to meth, became a drug dealer and eventually found Jesus Christ. He talked about his recovery from addiction and coming to a place of forgiveness for the driver who caused the crash.’

Elderly people and young mothers also shared stories of social isolation and feeling lonely, while other people shared about the impact of suicide or mental illness on their family.

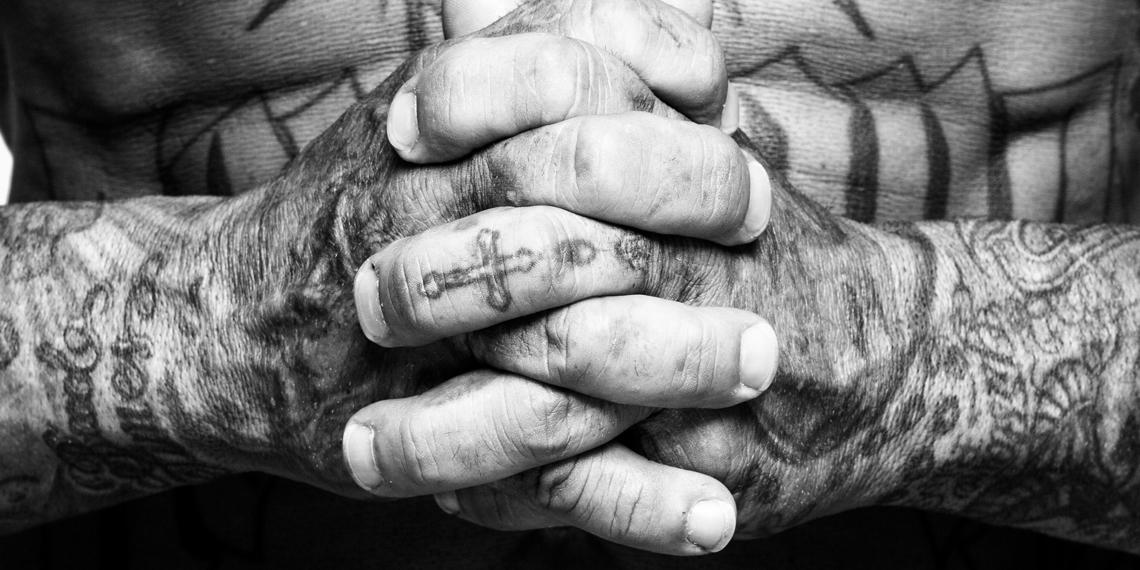

‘Stories like that were overwhelming, but also a great privilege. There was a man on a journey of recovery who had been in prison for 17 years. Another ex-prisoner and former gang member who talked about how his son is in the Mongrel Mob and isn’t allowed to come and visit him because he lives in a Black Power neighbourhood.’

The strongest theme across all the communities was concern about drugs and, in particular, about methamphetamine use, Ronji said.

‘People from all different ethnicities, ages and backgrounds were sharing how destructive it was. There was a young mum in Tīmaru who said she could get weed or meth in five minutes, it was that prevalent.’

The housing crisis was also a major concern, along with worries about a lack of opportunities for youth. People in most communities spoke about the need for opportunities to engage young people, to help them stay away from drugs and gangs.

A surprising area of concern was race relations, although this varied from community to community, he said. In Northland, people were concerned about tensions between Māori and Pākehā over issues of colonisation and poverty. Some also questioned the support being provided by some Māori organisations, Ronji said.

However, in Manurewa people spoke about racism towards people of Asian ethnicity, and in Tīmaru people noted the increasing cultural diversity of people being pushed south by the housing crisis and questioned whether others in the town would be welcoming to the newcomers.

A lack of mental health services, especially in Kaitaia and New Plymouth, was also raised, while violence, especially from gangs, was a particular concern for people in Manurewa.

There was hope in the report though and its outcomes, Ronji said. People had a clear idea of the building blocks of a strong community based around clear values, morals and connectedness, he said.

There was strong pride for each area, with people talking about a sense of home and community. They also talked about the many different ideas where people had taken ownership of the issues the community faced, and grass roots actions for addressing them.

‘There was Open the Curtains [where social workers go door-to-door helping families] and community pantries in the far north, self-defence classes in Hornby, parent groups in Tīmaru. They weren’t relying on local or national government to do things, they were coming up with their own solutions.’

The report gave an interesting insight into people’s views on the role and value of the church in their community.

‘There’s an increasing secularisation in New Zealand, at the same time, when asked about who was doing things to address the needs in the community, people were constantly coming back to the church—Christian organisations—even second-hand stores run by Christian groups. New Zealanders don’t want anything to do with the church, with the gospel message, but when it comes to their works they are accepted.’

Many people also advocated for a return to traditionally Christian values when they spoke about what made the building blocks of a good society, he said.

The report does not offer its own recommendations, allowing the people they interviewed to present the solutions themselves.

The Unit will also be going back to meet with each community this year to discuss the findings. The aim is to empower communities to come up with their own solutions, Ronji said. He was hopeful the report would be embraced by all six communities in the same way the first State of Our Communities, released in 2017, was embraced by the communities it covered—Linwood, Papakura and Porirua—and surrounding neighbourhoods.

In Linwood, the report was used to support the community’s appeal for a swimming pool that was eventually built. In Papakura, community groups had used the report to shape what they were doing—and surrounding areas had used it as a model to do their own surveys, he said.

The report has also been presented to parliament with a view to helping national and local government hear the concerns of the community. Collecting people’s stories added a human element—faces and voices that were important, alongside the number-based reports often presented to govenment, Ronji said. ‘We value the stories just as much as we value the numbers. We honour the voices that spoke on behalf of their communities.’

(c) by Robin Raymond 'War Cry' magazine, 26 January 2019 p14-15. You can read 'War Cry' at your nearest Salvation Army church or centre, or subscribe through Salvationist Resources.